“Spectra” Sample Explanation

Both The “Jones” Stick and The “Other” Stick had an “Infrared Spectroscopy Process” completed on them. This was completed to help identify the coating on each stick which would then help us pinpoint “when” the sticks were coated. The findings of this process would help us narrow down a birth year for the sticks. The process was completed to give us evidence to support our Radio Carbon Dating suggested age.

Firstly, a sample “Spectra” was taken as a baseline to make sure the Spectrometer was functioning the way it was supposed to be. It was.

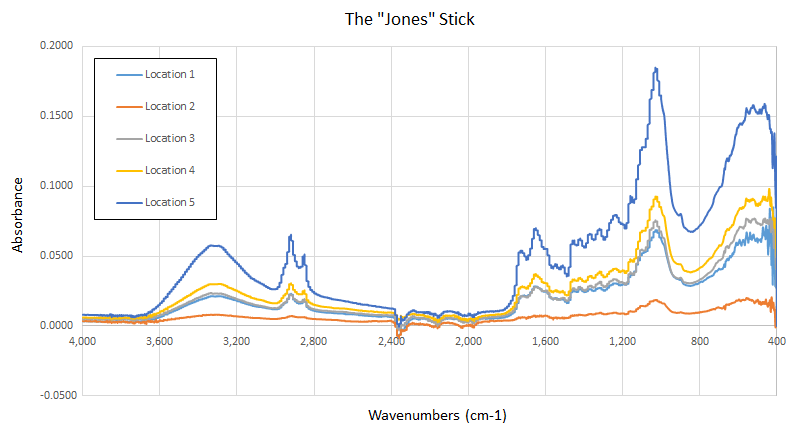

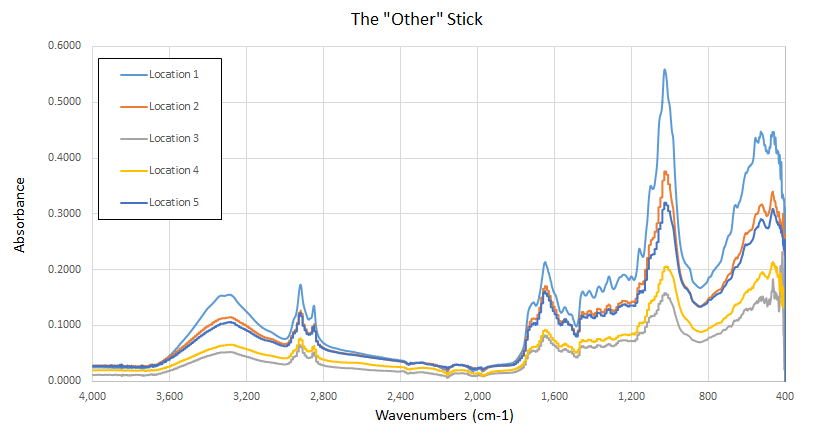

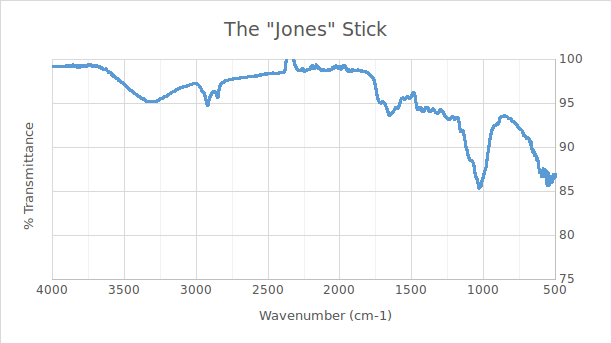

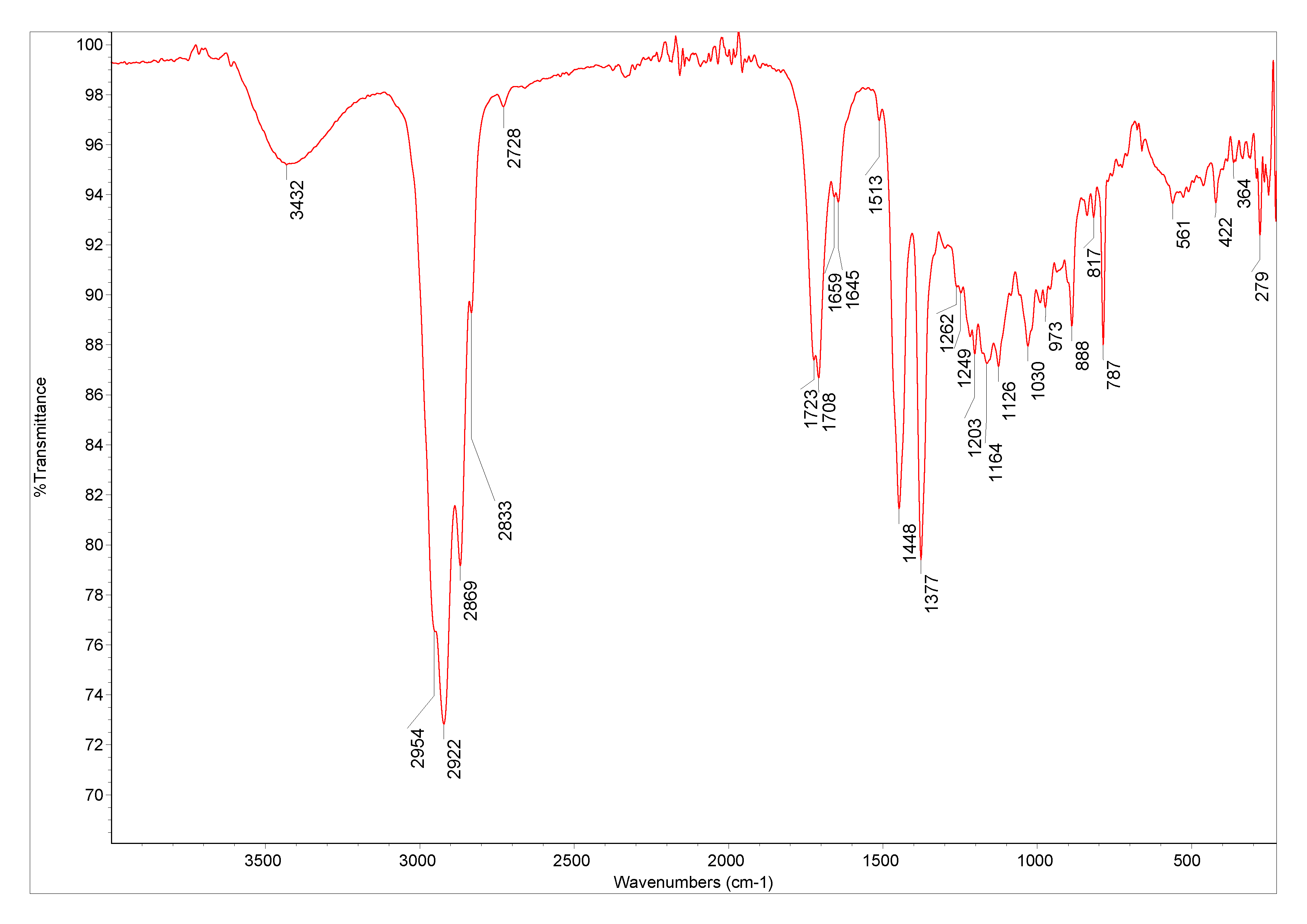

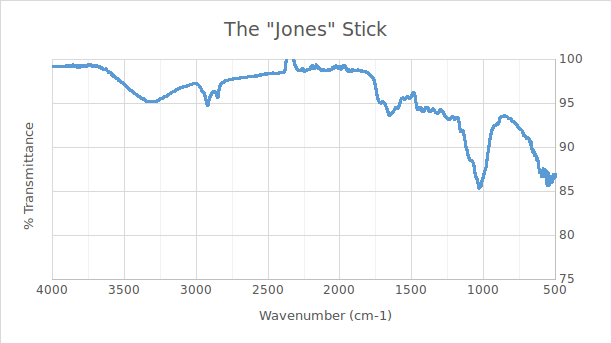

Then five “Spectra” samples were taken from different locations on each stick. The resulting “Spectra” above shows that the coating is indeed consistent in each of the five locations on the vintage hockey sticks.

We have the “Spectra” samples. Now, we have to have them fed through as database of coatings to see if we can identify what type of coating it is and the year range that coating was used on the historical timeline.

You can also see in these pictures the “Infrared Spectroscopy Process” as it was being completed on the two vintage hockey sticks.

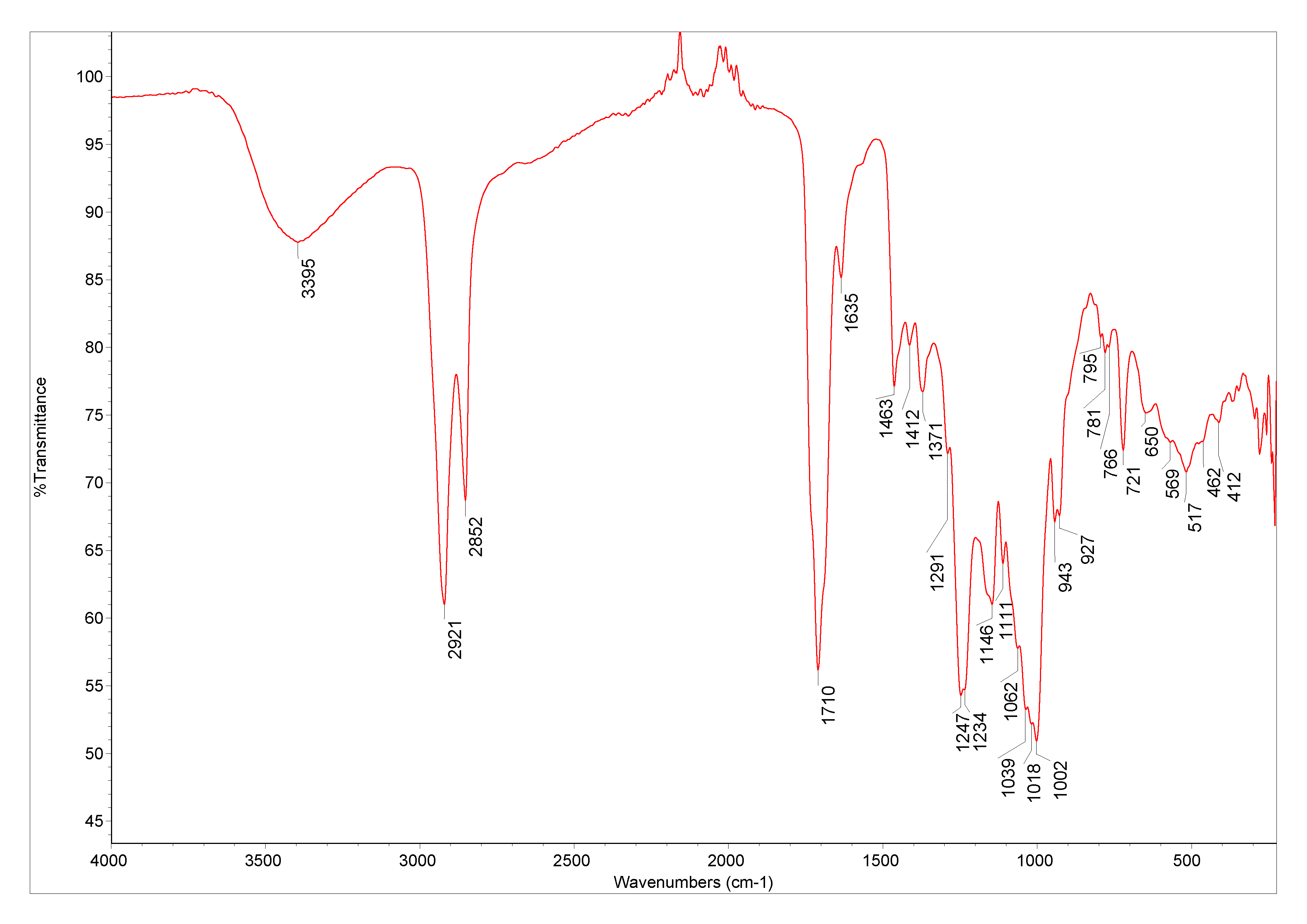

ATR-FT-IR spectrum of fresh Shellac:

ATR-FT-IR spectrum of fresh Dammar varnish:

http://antiquerestorers.com/Articles/jeff/shellac.htm SHELLAC – A TRADITIONAL FINISH STILL YIELDS SUPERB RESULTS

http://prorestorers.org/notes/earlyFinishes.htm Wood Finishes From 1600 – 1950

SHELLAC

“Shellac as a coating was used primarily from the early or mid-1800s until into the 1930s, when cellulose nitrate (or nitrocellulose) coatings started becoming popular.” Excerpt taken from “Shellac’s value stands the test of time” written by Greg William (http://www.woodshopnews.com/columns-blogs/finishing/498696-shellacs-value-stands-the-test-of-time)

Mussey says shellac was advertised as early as May 9, 1738 by John Merritt, whose ad called it “seedlach”, but there was no single purchase found in any account book until the early 1800s when it began to appear frequently. This may possibly be explained by its cost. Shellac was imported to Great Britain from India, then to the Colonies, and was subject to considerable import duties levied by the Crown. Beginning in the early 1800s the American merchant fleet began to import directly from the Far East and a huge trade developed, (Transparent Furniture Finishes in New England).

Don Williams says “Lac, the raw material from which shellac is made, is refined from the secretions of the tiny insect Laccifer Lacca, a native to Indochina and India. The Lac bugs live on trees, sucking out nutrients from the sap and secreting a protective shell that eventually covers the twigs and branches. When these deposits are abundant, the branches are cut off and the resin is prepared for processing. The raw material “sticklac,” is crushed and washed in water to remove the twigs, dirt and the lac dye in the insect carcasses. The finished product can include the amber color and the wax (which acts as a plasticizer) or can be blond (color removed) and dewaxed. The final step is assigning a grade to the shellac which is based on the host tree and the time of year it is harvested, wax content, color, clarity, and hardness”, (Shellac Finishing).

VARNISH

T. Hedley Barry, F.I.C. says “The history of the manufacture of varnish is necessarily associated with that of the arts and of industry. The application of a varnish is invariably the final stage in the preparation of an article for use, and as regards to both the quantity of the material and the labor involved, usually represents a comparatively small item. It is natural therefore that the manufacture of varnishes began as an incidental process, and in the early stages was ultimately connected with the arts rather than with industry. As to the nature of the varnishes used, we have in the works of Jean Felix Watin, a very detailed account of the types of varnish made and the method of manufacture. It was published in 1773, achieved great popularity and was re-edited no fewer than fourteen times, the last edition being published in 1906 by L. Mulo of Paris. The formulas are given in ounces and it is evident that the amounts made at one time were very small. In the case of spirit varnish, he recommends that the resin be dissolved in alcohol by heating on a water-bath whilst in the case of oil varnishes, he describes melting the resin in an earthenware pot, preferably glazed, over a hot fire, but not flaming. When the resin is properly run, the hot oil is added and heating continued until incorporation is complete. In fact, WatinÕs process is little more than a transcription of that described by; Theophilus at least 600 years before,” (Varnish Manufacture).

Mussey says Alcohol necessary for spirit varnishes was probably derived from various sources. While account books and newspaper advertisements rarely mention it, we know the colonies produced and exported huge quantities of rum and brandy, often high in alcohol content. Much of it was drunk but many varnish formulas specifically call for brandy as spirit vehicles, and its universal availability and cheap price probably led to its common use in spirit varnish. According to the Cabinet Makers Guide a typical varnish formula is “To one gallon of spirits of turpentine add five pounds of clear rosin pounded; put it in a tin can, on a stove, and let it boil for half an hour; when the rosin is all dissolved, let it cool, and it is fit for use”. This would have yielded a not-so-hard varnish with a decided yellowish brown tint. As turpentine and rosin are among the most frequently mentioned finishing materials encountered among entries in cabinetmaker’s account books of the period, and because they were among the cheapest, we can’t go far wrong in assuming a varnish such as this was commonly employed on much 18th and early 19th century furniture. The process was extremely simple, and required only domestically produced materials, free from the constraints of the various trade embargoes and taxation that imported resins were subject to. However, it would have been suitable only for darker woods. Another typical recipe recommends — To make the best white hard varnish: Rectified spirits of wine, two gallons; gum sandrach (a commonly used spirit varnish resin), five pounds; gum mastic, one pound; gum anime a relatively soft, Zanzibar copal mostly soluble in alcohol, four ounces; put these in a clean can, or bottle to dissolve, in a warm place, frequently shaking it, when gum is dissolved, strain it through lawn sieve, it is fit for use. The mixtures of old attempted to combine the best properties of the various resins and thereby to overcome the disadvantages of each. Sandarac was used for its lustrous quality; Venice turpentine to overcome brittleness; elemi resin for elasticity; copal gum for hardness; and benzoin as a plasticizer for the varnish. Another varnish from the Cabinetmakers Guide suggests 4 parts amber to 1 part gum lac dissolved in turpentine, with a small addition of linseed oil, (Transparent Furniture Finishes in New England).